The Fulmer family dogs died two by two.

Tasha slipped away in 2004 and Rocky passed with cancer three years after. They were Rhodesian ridgebacks. Alan and Patricia Fulmer and their children took in another pair as puppies, Zipporah and Ariel. They would succumb to cancer.

In 2018, the city of Sanford tested their well water and soon came back with results.

“They said don’t drink it, don’t cook with it, don’t brush your teeth with it, don’t bathe in it, don’t touch it,” Patricia Fulmer said, recalling that moment. “It was really scary.”

The Fulmers were blindsided repeatedly.

First, when they learned a chemical called 1,4-dioxane, deemed likely to cause cancer, was in their drinking water coming from their private, household well at a high concentration.

Then they found out officials had known for years that the chemical, linked to hazardous pollution at a former Siemens factory in Lake Mary, was contaminating the underground water supply – the Floridan Aquifer – in all directions around their home just south of Sanford.

The third shock was when Patricia Fulmer was diagnosed with a malignant tumor, adding to the stress of their two daughters coping with chronic illnesses and the passing of a fifth pet, Dunder, a miniature pinscher.

In 2021, they sold their home to a developer and moved away.

“It all began making sense,” said Patricia Fulmer, whose family has been firm in requesting a measure of privacy as they confront medical struggles and worries about their exposure to 1,4-dioxane. “It’s just so wrong.”

Her reaction has precedent in Florida. Some of the state’s most harrowing pollution episodes played out in stages: anxiety over exposure followed by distrust of officials for silence about a known threat.

1,4-dioxane was in use across the U.S. by the 1970s. The Siemens factory, making telephone network components, had been cited by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection the time it closed in 2003 for shoddy handling of hazardous chemicals.

There may be no way to learn when and at what strength 1,4-dioxane first invaded drinking water in Seminole County, but its presence was confirmed in the tap water of Sanford and the county’s Northwest Service Area in 2013 and in Lake Mary’s water in 2014.

Factory owners, including Siemens Corp. and General Dynamics, have denied liability for toxic pollution at the Lake Mary manufacturing site, but stated in 2017 that contaminants “may have been the result of historical activities at the Former Facility.”

‘You have the right to know’

The Fulmers were not alone in the dark.

Of the tens of thousands of residents and workers of Lake Mary, Sanford and Seminole County also exposed, it’s difficult to know how many have been made aware of the 1,4-dioxane they were consuming in drinking water.

It’s likely to be a very low percentage, judging from people well positioned to have learned of such a contamination of the Floridan Aquifer.

The Orlando Sentinel spoke with numerous people who have made it their profession and even passion to study and protect waters of Seminole County and the Orlando region.

Among them were Cathy Swerdlow, president of the League of Women Voters of Seminole County, a group that regularly analyzes water concerns. Another was Melanie Beazley, a chemistry professor at the University of Central Florida, who researches contamination of water sources in the region.

Neither had heard of 1,4-dioxane in the Floridan Aquifer and in drinking water, but now are eager to know more.

Nor was Gabrielle Milch, who has devoted much of her adult life to water concerns, aware of the chemical in the Floridan Aquifer.

Milch is a member of the Seminole Soil and Water Conservation District, education coordinator for the St. Johns Riverkeeper group and a former scientist at the St. Johns River Water Management District, the state’s lead caretaker for the Floridan Aquifer.

“I don’t think it’s fair that people were not informed,” Milch said. “They may not know what to do with the information. But I think you have the right to know.”

In seeking comments across the affected parts of Seminole County, the Sentinel did not encounter anyone who had heard of 1,4-dioxane in their drinking water.

Peter Geittmann, retired doctor of obstetrics and gynecology, and a member of his Heathrow neighborhood association board, said, “I’m certainly concerned about it and would like to learn more.”

Heathrow resident Brenda McClure said, “I think the county would let us know if it was serious.”

In historically Black Bookertown in northwest Seminole County, community association president Reginald Campbell said, “I would think they would have, or should have, let people know.”

In Sanford’s historically Black community of Goldsboro, Rudy Encarnacion, retired from the city’s water utility, and his wife Emma knew nothing of 1,4-dioxane. “They definitely should have told the water customers,” she said.

Echoes of Tallevast controversy

In many ways, the presence of 1,4-dioxane in Seminole County water is a replay of what happened in a place north of Sarasota, a drawn-out debacle described in some media as a scandal.

In 2000, the huge defense contractor Lockheed Martin reported to state authorities that its shuttered American Beryllium Co. plant, a maker of bomb parts, had polluted its grounds and underlying aquifer waters with toxic chemicals, including 1,4-dioxane.

The plant was in Tallevast, a historically Black community from the early 1900s of fewer than 100 homes today.

Three years after the Florida Department of Environmental Protection had been told of the pollution, Tallevast resident Laura Ward happened to look out from her son’s bedroom window at a looming, truck-mounted drilling rig in her yard.

“I walked out and asked him why they were there and what were they doing,” Ward said, recalling the moment that sparked grassroots action that has lasted 20 years so far. “One of the guys said, ‘well, there’s some contamination and we are trying to track it.’ That was how we were notified. We just happened to see the rigs.”

For three years, no authorities had warned Tallevast residents living a short walk from the Lockheed Martin plant to test their private, household water wells for the poisonous chemicals that were soon confirmed.

Even then, Ward and other residents were frustrated in getting answers to questions they barely knew how to ask.

“I started to call around to find out if there was someone who could tell me what’s happening and what’s going on,” Ward said. “Nobody could.”

A community group, Family Oriented Community United Strong, or FOCUS, organized to scrutinize and often oppose Lockheed Martin and state officials.

The group’s deep distrust for the corporation and government has waned little since their belated discovery of chemicals in drinking water.

Ward and another Tallevast resident, Wanda Washington, co-direct FOCUS. They’ve gotten support from volunteer students and environmental lawyers and recently obtained grants to support their efforts.

Their plight brought broader recognition. In 2005, the Legislature passed the “Tallevast bill,” requiring the state to notify property owners within 30 days of a potential pollution hazard.

The law was upgraded after a 2016 spill of contaminated water from a phosphate operation in Polk County drained into a sinkhole, triggering fears over drinking water. Now, anyone responsible for a pollution spill must submit a publicly available report within 24 hours.

Neither law applies to contaminants in utility drinking water.

“It’s not unusual, I think, for governmental agencies and others to keep what’s actually happening as quiet as they can, to keep it a secret from the people who are involved, and that’s not fair to residents,” Ward said.

“You want to know what you’ve been exposed to,” she said, “or to know the things that are happening in your life because of what someone else did.”

‘Synthetic Industrial Chemical’

Officials of Lake Mary, Sanford and Seminole County say they met their obligations to inform residential and business customers.

The utilities of the three governments found 1,4-dioxane beginning in 2013 as part of the EPA’s nationwide call for a one-time round of testing by utilities for research purposes.

The three utilities, as required by the EPA, printed their findings in 2015 and 2016 annual reports, called a “Consumer Confidence Report,” that community water providers must submit to customers.

The EPA this year began revamping consumer confidence reports “to increase the readability, understandability, and clarity of the reports.”

In 2015 and 2016, the information provided by the three utilities provided little for an ordinary person to grasp.

Seminole’s 2015 annual drinking water quality report, for example, stated that 0.41 parts per billion of 1,4-dioxane was discovered in county wells two years earlier.

Lake Mary and Seminole County used boilerplate wording from the EPA, stating the likely source of 1,4-dioxane was: “Cylic alipathic ether; used as a solvent or solvent stabilizer in manufacture and processing of paper, cotton, textile products, automotive coolant, cosmetics and shampoos.”

Sanford offered less: “Synthetic Industrial Chemical.”

All three utilities detected 1,4-dioxane concentrations that exceeded the health advisory level. There was no indication of that or of other health concerns.

Orlando Sentinel donating books about 1,4-dioxane to Seminole, Orange libraries

After 2016, the three utilities did not refer to 1,4-dioxane again in annual reports – they were not required to – even though from then on their drinking waters were tested several times annually, confirming the ongoing presence of the chemical.

As required by the EPA, the three utilities routinely are transparent with unwanted substances.

The EPA regulates 90 contaminants of a wide variety for drinking water, including, for example, benzene, pesticide, copper and nitrate.

Utilities must test for them and when they detect them, results must be stated in a Consumer Confidence Report, whether the concentration is above or even well below the allowable limit.

1,4-dioxane is not a regulated contaminant. But the chemical has been a candidate to be listed as one since 2008 and was designated by the EPA as likely to cause cancer in 2010.

“Communications about unregulated contaminants can build trust with the public,” said Greg Kail, spokesman for the American Water Works Association of utilities and professionals.

“It becomes a question of how do you provide people the context to make informed decisions,” Kail said. “They want to know what it means for them, what it means for their families.”

Sydney Evans, senior science analyst at Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit advocating for safe drinking water, lauded the utilities in Seminole County for reducing 1,4-dioxane in their tap water.

She said utilities are in limbo when it comes to the EPA not setting rules for chemicals such as 1,4-dioxane.

“Without health-protective regulations in place, it’s up to tap water utilities to protect public health as much as possible,” Evans said.

Protecting public health includes informing and educating consumers about contaminants in their water and about the steps taken to remove them, she said.

“Consumers have a right to know,” Evans said. “And when more consumers are empowered, polluters, utilities, and state and federal regulators can be held accountable.”

Lake Mary stands by its actions to inform its customers: “The information was included in our Annual Water Quality Report from the time it was first sampled for,” said Danielle Koury, the public works director.

This year, Sanford began to post on the city’s water and sewer website a section that describes 1,4-dioxane.

It notes that it was spilled at the Siemens factory, but does not say it is classified as likely to cause cancer.

“The city is aware of the presence of contaminants (1,4-dioxane) that were discharged from a decommissioned site (former Siemens site) in Lake Mary,” according to a section about 1,4-dioxane added to the city’s website this month. “1,4-dioxane was used and discharged at the former Siemens site in Lake Mary.”

Seminole County’s regard for transparency is now a work in progress among senior leadership and county commissioners, having been questioned by the Orlando Sentinel about 1,4-dioxane.

Commissioner Andria Herr, whose district includes the Northwest Service Area and her neighborhood of Heathrow, said she favored putting a notice on a dashboard of the county’s website about 1,4-dioxane.

“We have to strike the balance between keeping people informed — which I think a dashboard would do — and sending out an alert that says ‘heads up, we have a problem,’” Herr said.

On Wednesday, a day after Part 1 of Toxic Secret was published online, the county posted a brief explanation of 1,4-dioxane in its water and its plan to begin more frequent testing of water quality.

Ugly acres

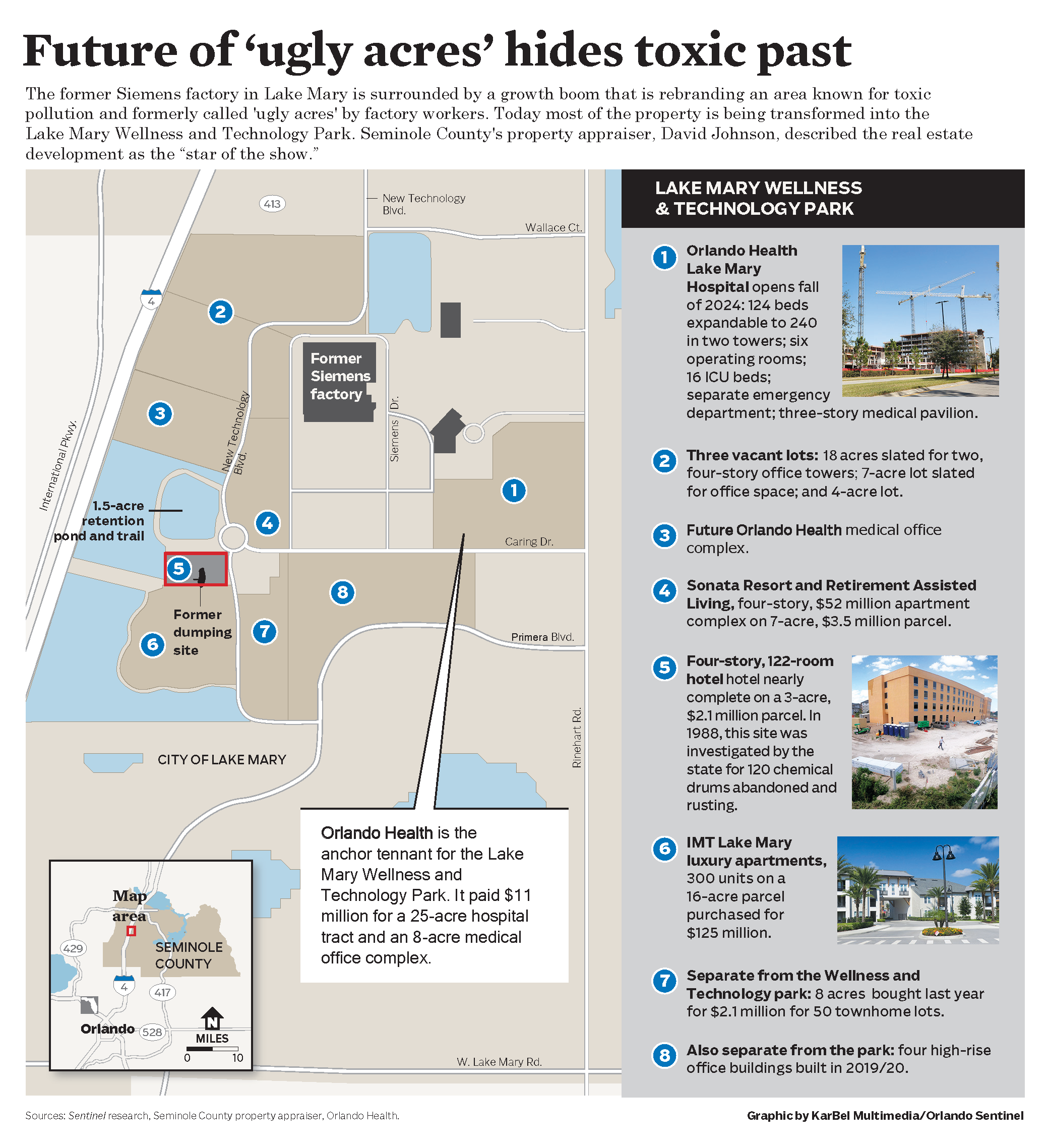

With 1,4-dioxane in Seminole County drinking water long shrouded in obscurity, now the suspected source of it all, the Siemens factory, is being hidden by the glass and concrete of an emerging brand of health and technology.

While the Siemens factory was still in operation, workers spoke of the landscape around their workplace as “ugly acres.”

It was bleak scrubland with a toxic dump site, dense brush, skeletal remains of dead citrus grove and motorcycle tracks. A modest recreation area of clay volleyball courts, picnic spot and barbecue grill were tucked between the toxic dump and a pond.

Today, the “ugly acres” are being transformed into the Lake Mary Wellness and Technology Park, rising as a curtain on nearly all sides around the low-slung and still-standing Siemens plant.

The development project’s entrance, Caring Way, passes within feet of the city of Lake Mary’s defunct water well No. 5. It was shut down after a decade of providing large volumes of water because it was found to contain a strong dose of 1,4-dioxane.

Caring Way ends at a traffic circle at the edge of an area measuring 100 feet by 300 feet that investigators in the late 1980s cordoned off as a hazardous dumping place of chemical drums.

Today, construction crews are finishing a four-story hotel built on top of the drum site within a 2.8-acre parcel that sold two years ago for $2.1 million.

Also constructed or in the works on the ugly acres: the Sonata Resort Retirement and Assisted Living; IMT Lake Mary luxury apartments; a pair of four-story office towers; and the Orlando Health Lake Mary Hospital slated for opening next year with a five-story and a six-story tower. It will stand next to the hospital’s new two-story emergency facility and three-story medical pavilion that opened in 2017.

Seminole County’s property appraiser, David Johnson, said the Wellness and Technology Park has been a resurrection: the scruffy outskirts of an infamously toxic site converted into a powerful engine for the county’s economy.

“It’s a star of the show,” Johnson said, of the sale prices for vacant land and the intensity of development occurring. “Those are marquee-type of properties.”

He described the former “ugly acres” surrounding the Siemens factory as “some of the more valuable property in the county.”

What if?

Also, about to be paved over is where the Fulmers lived a mile north of the factory.

The Fulmers sold their house two years ago. It and a remarkable canopy of oaks, cherry trees and pines were bulldozed down to bare dirt this summer.

The Fulmer home, perhaps the only in Seminole County where its residents have worried about 1,4-dioxane exposure, will be replaced by a self-storage business.

The family moved away from the area, knowing they will always wonder if they were too late in learning of the chemical.

Toxic Secret: Our series about 1,4-dioxane in Seminole water

- Part 1 – A toxic chemical, 1,4-dioxane, has infiltrated waters of three utilities.

- Part 2 – Local water utilities have struggled with how to address 1,4-dioxane, a likely carcinogen.

- Part 3 – 1,4-dioxane has a seemingly sinister ability to invade the Floridan Aquifer.

- Part 4 – 1,4-dioxane in Seminole water has been a virtual secret. How one family found out

Know more about this issue?

Do you have pertinent information about the 1,4-dioxane contamination in Seminole County water you would like to share with us for our reporting? If so, please email us at toxicsecret@orlandosentinel.com.

About the journalists who reported this series

- Kevin Spear is the Orlando Sentinel’s environmental reporter. He has been with the newspaper for 34 years and for most of that time has covered key issues relating to water, wildlife and land use. He can be reached at kspear@orlandosentinel.com

- Caroline Catherman is the Orlando Sentinel’s health reporter. She joined the newspaper in 2021 after previously working in public health research. She can be reached at ccatherman@orlandosentinel.com

- Martin E. Comas is the Orlando Sentinel’s Seminole County reporter. He started at the newspaper in 1988 and has covered key Seminole stories including the death of Trayvon Martin and its aftermath, and the controversies surrounding disgraced Tax Collector Joel Greenberg. He can be reached at mcomas@orlandosentinel.com

- Joe Burbank is the Orlando Sentinel’s senior photographer. He joined the newspaper in 1988 after working for Agence France-Presse news. He has spent more than three decades covering Central Florida with his visual reporting. He can be reached at jburbank@orlandosentinel.com

- Rich Pope is the Orlando Sentinel’s videographer. He joined the newspaper in 2003. He has received Emmy nominations, along with recognitions from the Online News Association and Florida Society of Newspaper Editors. He can be reached at rpope@orlandosentinel.com

Help support our investigative reporting

Contributions to the Orlando Sentinel’s Community News Fund helped us produce this series. Please consider supporting our reporting by donating to the fund at OrlandoSentinel.com/donate

![By MEAD GRUVER (Associated Press) The human species has topped 8 billion, with longer lifespans offsetting fewer births, but world population growth continues a long-term trend of slowing down, the U.S. Census Bureau said Thursday. The bureau estimates the global population exceeded the threshold Sept. 26, a precise date the agency said to take with […] By MEAD GRUVER (Associated Press) The human species has topped 8 billion, with longer lifespans offsetting fewer births, but world population growth continues a long-term trend of slowing down, the U.S. Census Bureau said Thursday. The bureau estimates the global population exceeded the threshold Sept. 26, a precise date the agency said to take with […]](https://www.orlandosentinel.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/India_Festival_49284.jpg?w=525)